Giant Phantom Jellyfish: Rare 2026 Sighting Stuns Scientists

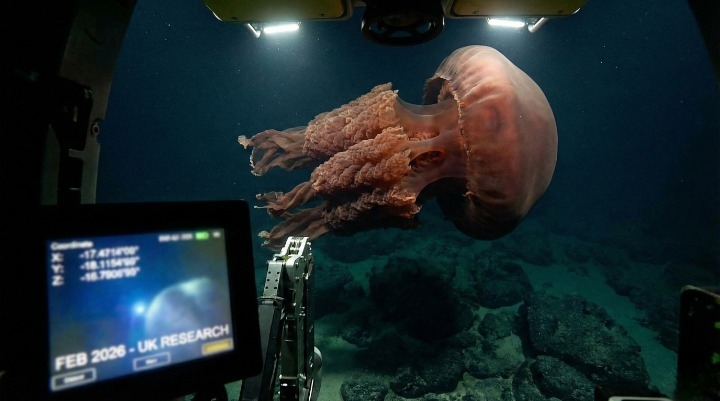

Imagine piloting a remotely operated vehicle (ROV) thousands of metres beneath the ocean surface. The darkness is absolute, broken only by the artificial glare of your sub’s floodlights. Suddenly, a massive, billowing shape drifts into view. It isn’t a rock formation or a whale, it is a “crimson curtain” of living tissue, pulsating silently in the abyss.

This is the giant phantom jellyfish (Stygiomedusa gigantea), one of the deep ocean’s most elusive and spectacular predators.

For over a century, this creature was little more than a rumour. Sightings were so scarce, fewer than 130 recorded in 110 years, that marine biologists referred to it as a ghost. But that changed in February 2026.

In a groundbreaking expedition off the coast of Argentina, scientists aboard the Schmidt Ocean Institute’s R/V Falkor (too) captured stunning, high-definition footage of a giant phantom jellyfish. This encounter didn’t just add a tally mark to the sighting record; it rewrote what we know about their behaviour, depth range, and survival in the “Midnight Zone.”

Here is the complete briefing on Stygiomedusa gigantea, from its alien anatomy to the British explorers who first discovered it.

What is the Giant Phantom Jellyfish (Stygiomedusa gigantea)?

The giant phantom jellyfish is the largest invertebrate predator in the deep ocean ecosystem. It belongs to the class Scyphozoa (true jellyfish) and the family Ulmaridae. Taxonomically, it stands alone; it is the only species in its genus, making it a monotypic organism. Evolution created this specific design once and apparently decided it could not be improved.

A Monotypic Mystery

Why is there only one species of Stygiomedusa? Genetic analysis suggests this creature occupies a highly specific ecological niche. While other jellyfish families branched out into dozens of varieties, the giant phantom remained singular. Its scientific name, Stygiomedusa, nods to the River Styx from Greek mythology, the dark boundary between Earth and the Underworld. It is a fitting title for an animal that patrols the eternal darkness of the bathypelagic zone.

The “Phantom” Name

The “phantom” moniker isn’t just about its rarity. It refers to the way the animal moves. Unlike energetic surface jellies that pulse rapidly, the giant phantom drifts with a slow, hypnotic rhythm. Its massive oral arms trail behind it like tattered silk sheets, creating a spectral silhouette against the black water.

[Watch the 2026 Schmidt Ocean Institute footage here]

Anatomy of a 10-Metre Deep-Sea Ghost

To truly grasp the scale of a giant phantom jellyfish, you have to look beyond standard measurements. Numbers on a page rarely do justice to a creature that can rival the largest marine mammals in length.

Oral Arms vs. Stinging Tentacles

Most jellyfish are feared for their sting. Stygiomedusa gigantea operates differently. It lacks the venomous nematocysts (stinging cells) found on the tentacles of species like the Lion’s Mane jellyfish.

Instead, it possesses four colossal oral arms. These are not thin tentacles but thick, ribbon-like folds of digestive tissue. These arms drape down from the bell, acting like sticky traps. When the jelly encounters prey, usually plankton or small fish, it uses these billowing folds to ensnare the victim and transport it upward to the mouth.

Expert Insight: Think of these arms less like harpoons and more like a moving net. They create a massive surface area, allowing the jellyfish to “trawl” the water column passively. This energy-efficient feeding strategy is crucial in the deep sea, where food is scarce.

The Double-Decker Comparison

For our UK readers, the size of this animal is best visualised on the street. The main body, or bell, can grow more than 1 metre (3.3 feet) wide. That is roughly the width of a large round dining table.

But the arms are the real showstopper. They can extend over 10 metres (33 feet) in length. If you were to drape a giant phantom jellyfish over a standard London double-decker bus, the bell would cover the driver’s cab, and the arms would trail all the way past the rear platform.

The Science of Invisibility: Why is the Phantom Jelly Red?

If you look at photos from the R/V Falkor (too) or MBARI (Monterey Bay Aquarium Research Institute), the jellyfish appears a deep, vibrant crimson or reddish-brown. This isn’t a fashion statement; it is advanced optical physics.

Porphyrin Pigments and the Midnight Zone

Sunlight is composed of a spectrum of colours. Water absorbs these colours at different rates. Red light has the longest wavelength and the lowest energy, meaning it is absorbed first. By the time you reach 200 metres deep, red light is gone.

In the bathypelagic zone (1,000–4,000 metres), the ocean is pitch black. However, many deep-sea predators use bioluminescence, producing their own blue-green light, to hunt.

Here is the trick: In blue light, red objects appear black. The giant phantom jellyfish is coloured by porphyrin pigments that make it virtually invisible in its natural habitat. To a predator scanning the dark with biological searchlights, the giant phantom jellyfish is simply a shadow in the void. It is the ultimate camouflage.

Rare 2026 Sighting: The R/V Falkor (too) Expedition

The oceanographic community was sent into a frenzy in February 2026 during an expedition off the coast of Argentina. The team aboard the Schmidt Ocean Institute’s vessel, R/V Falkor (too), was mapping unexplored canyons when their ROV, SuBastian, picked up a massive signal.

The Colorado–Rawson Canyon Discovery

The team was exploring the Colorado–Rawson Canyon complex, a steep underwater valley system. They expected to find cold seeps and coral gardens. Instead, they filmed a pristine Stygiomedusa gigantea gliding past the camera.

This sighting was significant for two reasons:

- Image Quality: The 4K footage provided the clearest look yet at the texture of the bell, revealing small bumps and ridges previously unknown to science.

- Behaviour: The jelly was observed “rowing” against a mild current, proving that despite their gelatinous form, they are strong swimmers capable of navigating complex canyon hydrodynamics.

Depth Anomalies

Historically, we assumed these jellies lived strictly below 1,000 metres. However, the Argentina sighting, and recent data from the Southern Ocean, recorded the specimen at just 250 metres.

This suggests that in colder, nutrient-rich waters (like those off the Falklands or Antarctica), the giant phantom jellyfish migrates much closer to the surface. It challenges the textbook definition of them being purely “abyssal” creatures. They go where the food is, pressure be damned.

Reproduction Secrets: Do Giant Phantom Jellyfish Give Birth?

Most jellyfish spawn by releasing clouds of eggs and sperm into the water, hoping for the best. It is a “spray and pray” strategy. The giant phantom jellyfish, however, is a devoted parent.

Viviparity in Jellies

Research published in the Journal of the Marine Biological Association of the UK confirms that Stygiomedusa gigantea is viviparous. This means it gives birth to live young, a trait extremely rare in Cnidarians.

The Four Brood Chambers

The female jellyfish possesses four specialised brood chambers located inside the gastric system. The embryos develop here, protected from the harsh open ocean. They grow into scyphistomae (the polyp stage) or even juvenile medusae before they are released.

This strategy ensures a higher survival rate for the offspring. In the vast emptiness of the deep sea, finding a mate is hard, and ensuring your larvae survive is even harder. By brooding their young, giant phantoms give the next generation a fighting chance.

Symbiosis in the Abyss: The Jellyfish’s “Roommates”

The giant phantom jellyfish rarely travels alone. It often serves as a mobile hotel for other species.

The Pelagic Brotula (Thalassobathia pelagica)

One of the most fascinating discoveries by MBARI is the symbiotic relationship between the phantom jelly and the pelagic brotula fish.

This small fish lives inside the massive bell of the jellyfish. It swims among the oral arms, using the jelly for protection. In the open ocean, there are no caves or coral reefs to hide in. The giant phantom offers the only cover for miles.

The relationship is likely mutualistic:

- The Fish: Gets protection and scraps of food caught by the jelly.

- The Jelly: May benefit from the fish removing parasites from its bell, although this is still being studied.

A Legacy of Discovery: The UK’s Link to the Phantom Jellyfish

While modern ROVs like SuBastian get the glory today, the story of Stygiomedusa gigantea has deep roots in British exploration history.

From Scott’s Discovery Expedition to the NHM

The first specimen was collected in 1899, but the most significant early finding came during the British National Antarctic Expedition (1901–1904), led by Captain Robert Falcon Scott. The expedition ship, Discovery, hauled up a massive, fragmented jelly from the Southern Ocean.

Edward Adrian Wilson’s Illustrations

The expedition’s junior surgeon and zoologist, Edward Adrian Wilson, meticulously documented the find. Though originally classified under a synonym (Diplulmaris gigantea), these early British records provided the physical holotype stored at the Natural History Museum in London.

It wasn’t until 1960 that the species was formally recognised as Stygiomedusa gigantea. Every time a modern scientist identifies one, they are referencing groundwork laid by UK explorers over a century ago.

FAQs

How many giant phantom jellyfish are there in the world?

We do not have a population estimate. Given their global distribution (found in every ocean except the Arctic) but low sighting numbers, they are likely widespread but solitary.

Does the giant phantom jellyfish sting?

No. It lacks stinging nematocysts. It uses its massive oral arms to trap prey mechanically rather than chemically.

What does the giant phantom jellyfish eat?

Its diet consists mainly of plankton, small fish, and other gelatinous creatures.

Where can I see a giant phantom jellyfish?

You cannot see them in aquariums; they cannot survive the low pressure and walls of a tank. The only way to see one is via deep-sea submersible expeditions or ROV footage.

How big is the bell of a Stygiomedusa gigantea?

The bell typically reaches 1 metre in width, but the arms make the animal appear much larger.

Is the giant phantom jellyfish endangered?

It is currently “Not Evaluated” by the IUCN. However, deep-sea mining poses a significant threat to their habitat.

Why do they look like ghosts?

Their slow movement, lack of visible internal organs, and billowing, sheet-like arms give them a spectral appearance in the water.

The Fragile Giants of the Deep

The February 2026 sighting off Argentina reminds us that the ocean is still largely undiscovered. For every Stygiomedusa gigantea we catch on camera, there are likely thousands moving unseen through the dark.

These creatures are masters of adaptation. They have conquered the cold, the crushing pressure (up to 5,800 psi), and the eternal night. Yet, they remain vulnerable. As humanity pushes for deep-sea mining and bottom trawling, we risk destroying these ecosystems before we even fully understand them.

The giant phantom jellyfish is more than a viral video or a spooky statistic. It is a vital piece of our planet’s biological heritage, a silent, velvet giant drifting through the last great wilderness on Earth.

[Support ocean conservation with the Marine Conservation Society UK]